Historical Calendars and Advances in Agriculture

By: Miko Brandon

As humans we constantly feel the pressure of time. Our ceaseless desire to glance at our clocks. “Is it 5 o’ clock yet?” It seems time moves in inches when we’re doing the things we loathe. Yet zips by when we’re immersed in the activities we enjoy: birthdays, seasonal ceremonies *cough* Oktoberfest *cough*, dental appointments, retirement. Counting the days is fundamental to human existence. We use a number to represent a specific moment in our lives, then use other numbers to make somewhat accurate predictions on the future. You can use the number to figure out how old grandma is or estimated the best time to plant your corn. These basic principles were ingrained in us by the ancestors before us. Ancient civilizations laid the foundation of counting the days with one of humans most useful tools… the CALENDAR! And with the ability to count and predict seasonal changes, the calendar allowed for the advancement of civilization’s agriculture.

Mesopotamia: Some may call the ancient Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia the founding Fathers of the calendar, aka the “OG’s.” The wise astronomers of ancient Mesopotamia are said to be the first to use the lunisolar calendar. 360 days, 30 days a month, and 12 months a year made up the calendar (Russell, 2022). The Sumerians could use the calendar to determine the seasons. Emesh (summer) which started around late February or early March, and Enten (winter) which started late September or early October. The seasonal predictions also allowed them to predict wet and dry seasons (Abit, 2022. Slide 14). This led to agricultural advancements such as flood levee construction. This prevented crop damage during flood seasons and allowed for the retention of some water for drier seasons. Agriculture was extremely important to the Sumerian civilization and a great contributor to their growth. Arguably, growth would not have been possible without the calendar

Ancient Egyptians: Was it Aliens? Nah probably not. The ancestors of ancient Egypt developed a solar calendar that had 12 months and 365 days a year. Sounds a lot like the calendar we use nowadays. It also had three seasons; a bit different from the four seasons we commonly recognize today. But what even is a “season”; is it something humans use to describe daylight hours and weather patterns or is it something we put on chicken? Both. The first season was akhet, representing the time which the Nile floods. Second was peret, the time when crops broke through the fine soils. Last was Shemu, the harvest time (Egyptian civilization, 2022). Understanding when the Nile floods allowed ancient Egyptians to predict when the best time to plant was. Once water subsided, the area left was plump with nutrients. Success in agriculture leads to growth, and growth, leads to innovation. One example is the ox-drawn plow. Created in ancient Egypt, the plow, pulled by ox broke up the earth and prepared it for seed planting. This advancement allowed Egypt to produce loads of crops and become known as the “breadbasket of the Roman Empire” (Mark, 2022)

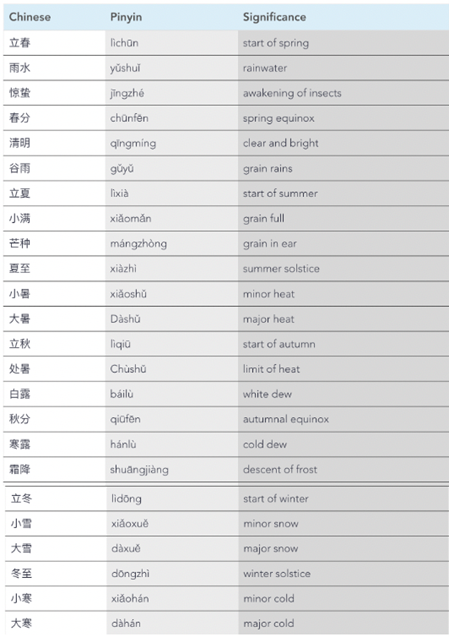

Chinese lunisolar calendar that can trace its origins back to the Han dynasty 104 BC.

Chinese lunisolar calendar that can trace its origins back to the Han dynasty 104 BC.

Ancient Chinese: If it ain’t broke don’t fix it! The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar that can trace its origins back to the Han dynasty 104 BC. This is the same calendar that is used and of great importance to China today. The year is broken up into 24 solar terms, each reflecting seasonal changes and revolving itself around agriculture (Yeromiyan, 2022). Being able to make accurate assumptions on rainy seasons, intense heat, frost or even insects allow the farmers to know when to plant and harvest. The ability to have successful crop production led to many agricultural advancements such as the invention of paper, the wheelbarrow, and iron plows. Specifically, the moldboard plow allowed the ancient farmers to work in sloped areas while reducing their soil loss (Kiger, 2019).

Ancient Mayan calendar

Ancient Mayan calendar

Ancient Mayans: I remember back in 2009 — I believe I was in 9th grade — we all went to see the movie “2012.” We were certain the world was going to end. The ancient Mayan calendar supposedly ended abruptly in December of 2012. We thought we only had a few more years before the inevitable. Maybe the world did end in 2012. Maybe we’re all living in some weird alternate reality, with reality TV stars as Presidents, really hot summers, and pangolins. Maybe the Mayans just thought 2012 was pretty far out and they would finish the rest later. Or maybe they had other things to worry about. The light-skinned guys showing up on giant floating houses, riding big deer looking things could’ve been pretty distracting. Either way, the ancient Mayan calendar was amazing and insanely accurate. The calendar dates to around the first century BC and is ever so slightly more accurate than the calendar we use today. It consists of 20-day months with two calendar years. First, tzolkin, which is 260 days and second, haab, which is 365 days. The two link up at 18,980 days or about 18 months (Canadian , 2022). There was a belief that an individual’s future could be predicted based on the time they were born. For agriculture, the sun, corn, and calendar were intertwined (Méndez, 2022). This a allowed them to keep track of planting and harvest times. Calendar predictions lead to agricultural advancements like intercropping and agroforestry practices, but the result of successful agriculture led to something really cool: ball courts. Mayans would gather to watch the athletes and prisoners play intense ball games such as pok-a-tok (Adhikari, 2022). You don’t have time to innovate sweet games if your basic needs aren’t met. The calendar helps meet those needs.

Final Thoughts: To be frank, calendars are dope. One day the people of the future will dig up our calendar and say things in wonder. They’ll say “the ancient monkey humanoids of 2022 used bi-fold paper calendars decorated with puppies and half naked firefighters.” They will talk in amazement of how we used our calendar to predict the first frost, wedding dates, or how we used the sun to correspond to a day where an egg laying rabbit hides candy filled synthetic polymer-based ovum throughout residential areas.

Reference List:

- Adhikari, S. (2022, August 31). Top 10 inventions of the Mayan Civilization. Ancient History Lists. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.ancienthistorylists.com/maya-history/top-10-inventions-of-mayan-civilization/

- Egyptian civilization – sciences – calendar. Canadian Museum of History. (n.d.). Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/civil/egypt/egcs02e.html

- Kiger, P. J. (2019, September 20). 10 inventions from China’s Han dynasty that changed the world. History.com. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/han-dynasty-inventions#:~:text=According%20to%20Robert%20Greenburger’s%20book,known%20as%20the%20moldboard%20plow.

- Mark, J. J. (2022, September 8). Ancient Egyptian agriculture. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/997/ancient-egyptian-agriculture/

- Russell, J. (2022, September 1). The Sumerian calendar. Living With The Moon. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.livingwiththemoon.com/origins-of-the-calendar/

- Yeromiyan, T. (2022, March 27). What is the Chinese calendar?: The Chinese Language Institute. StudyCLI. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://studycli.org/chinese-zodiac/chinese-calendar/

Disappearance of the Aral Sea

By: Molly Hoback

What would you do if your seaside community suddenly lost its sea? Over a couple of decades, day by day you watch in futile horror as your shores recede step by step and mile by mile until there is no trace that water was ever here. All that is left is a salty, toxic wasteland, dotted with rusting, abandoned boats like gravestones in a field. As the sea vanishes, your vibrant community fades. Hope dies. Food becomes scarce and fishing becomes impossible without traveling tens of miles. Seasons become erratic, and crops begin to fail. Livestock and people develop health problems as they inhale toxic chemicals in frequent dust storms. Respiratory diseases and cancers become common and mortality rates increase. Such is the story of more than 3.5 million people who depended on the Aral Sea.

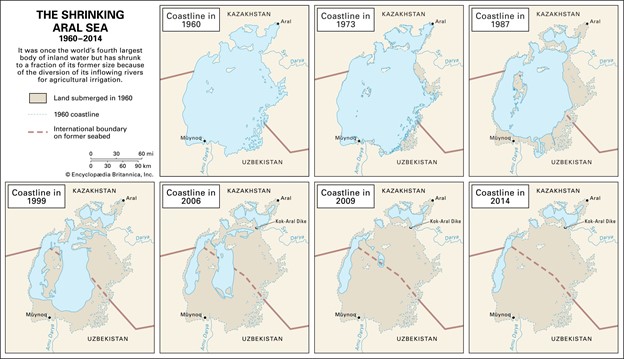

For all of recorded history, the Aral Sea had been an enormous saltwater lake. Its historic boundaries span it across the modern-day border of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In its heyday, the Aral Sea covered more than 26,000 square miles and produced more than 48,000 tons of fish each year (Carylsue). Beginning in the 1960s, the sea began to fragment and disappear (Fig. 1). By 1999, environmental experts had deemed the Aral Sea unsavable. Today, two remnant bodies, the North Aral Sea and South Aral Sea remain. According to the United Nations Development Programme, the Aral Sea’s decline was, “the most staggering disaster of the twentieth century” (Grabish). Such a statement not an exaggeration when considering that only forty years prior, the lake had been the fourth largest in the world. In fact, the Aral Sea had maintained relatively steady water levels and areas for nearly two thousand years (“Aral”). So, what had happened to cause such rapid depletion, and what impacts did its disappearance cause for the land and its people?

Figure 1: Visual display of the decrease in the size of the Aral Sea. (Image from “Aral Sea”)

Figure 1: Visual display of the decrease in the size of the Aral Sea. (Image from “Aral Sea”)

The Cost of Cotton and the Siphoning of Rivers:The rapid decline of the Aral Sea dates back to 1959 when the Soviet Union chose Central Asia to become its cotton supplier. In twenty years, Central Asia was the fourth largest producer of cotton with an annual rate of nine million tons of cotton. To grow cotton, vast amounts of water is required. For Central Asia, that water was siphoned from the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers. These rivers were what fed the Aral Sea (Grabish). The rivers’ water turned arid deserts of present-day Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan into blooming cropland (“World”). In return, the over a stunningly short period of time, thriving fishing industries around the sea failed as the water levels dropped and the remaining water became increasingly saline. The sea practically vanished. Furthermore, Soviet policies broke existing water policies that prevented overuse.

The Dismantling of Existing Water Management Systems: Before Soviet intervention, mirabs, or water masters, controlled the water resources of much of Central Asia. They ensured proper and fair water allocations and were driven by a local proverb, “in every drop of water there is a grain of gold” (Grabish). Quite abruptly, the mirabs lost power over the water supply and local farmers were encouraged to exploit the water and land to produce the most cotton as possible. Areas of depleted soils were abandoned, and fertilizer run-off devastated lands downstream. A local sense of accountability for the water resource all but vanished. So, too, did the Aral Sea. The result was economically devastating for those who used to live on the shorelines, but physically devastating for many more. Negative health impacts abounded alongside the environmental fallout caused by the receding shores of the Aral Sea.

Figure 2: Beached vessel in the salt flats left by the receding sea. (Image from “Aral Sea”)

Figure 2: Beached vessel in the salt flats left by the receding sea. (Image from “Aral Sea”)

The Environmental Consequences of a Disappearing Sea: With the water gone from the Aral, vast salt plains remained (Figs. 2 & 3). These salt plains contained toxic salts and minerals like sodium chloride, sodium sulfate, and magnesium chloride. The increasingly salty water disappeared, leaving dangerous fertilizers and pesticides (“World”). As the lake receded, salt flats spread for more than sixty miles and wind blew more than forty million tons of dried salt into agricultural lands (Carylsue). Such toxic salts destroyed crops, but also damaged human health. In increasing rates, people of Central Asia faced anemia, respiratory and intestinal ailments, and infant and maternal mortality. Climate change was also an inevitable outcome of the loss of the Aral Sea. Without the large, regulatory body of water, seasons became more extreme with summers becoming hotter, drier, and longer, with winters becomes more bitter and dry (Grabish). With dire consequences emerging from the loss of the Aral, and its salvation evidently out of reach, many abandoned goals of rejuvenating the sea and turned to helping the people devastated by the loss of the Aral instead. Nonetheless, a portion of the Aral Sea was saved.

Figure 3: Abandoned vessels lying in the desert that was once the Aral Sea. (Image from “The Country that Brought a Sea Back to Life”)

Figure 3: Abandoned vessels lying in the desert that was once the Aral Sea. (Image from “The Country that Brought a Sea Back to Life”)

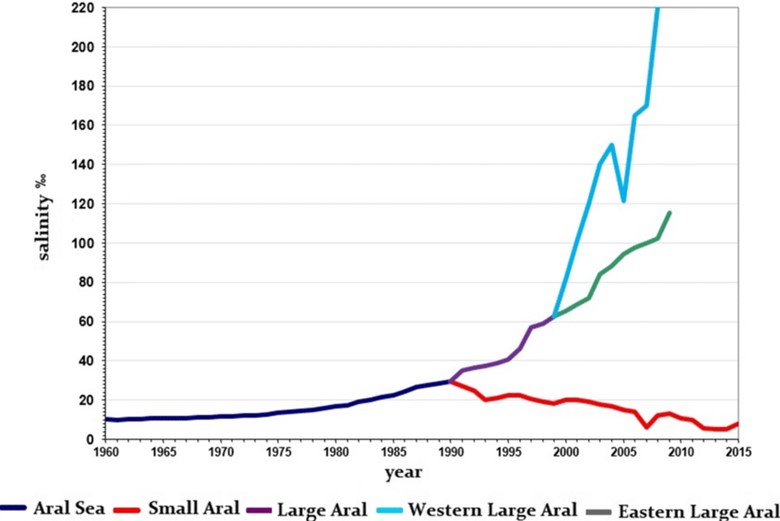

The Salvation of the North Aral Sea: By the early 2000s, the Aral Sea had been split into the North Aral Sea and the South Aral Sea. A major dam, the Kok-Aral, began to revive the North Aral Sea upon its completion in 2005. Between 2005 and 2018, water levels in the North Aral Sea rose by approximately twenty percent and the fishing industry went from producing 1,360 tons of fish to 8,200 tons. Furthermore, the North Aral Sea has drastically decreased in salinity, which is reviving the aquatic ecosystem (Carylsue). This drop in salinity for the North Aral can be seen in Figure 4. The Aral Sea had always been a saltwater lake, but historically, it had been briny enough to support many freshwater fish. Today, many freshwater fish are beginning to be reintroduced to the North Aral Sea, much to the delight of local markets and those abroad. Hope has returned to the North Aral Sea, even as the desiccated and depleted South Aral Sea continues to vanish, leaving devastated, sick communities surrounded by toxic sand and the beached remains of long-abandoned vessels.

Figure 4: Chart showing overall salinity increase. Note the Small Aral Sea (the North Aral) has decreased in salinity. (Figure adapted from a “The Zoocenosis of the Aral Sea” image)

Figure 4: Chart showing overall salinity increase. Note the Small Aral Sea (the North Aral) has decreased in salinity. (Figure adapted from a “The Zoocenosis of the Aral Sea” image)

Conclusion:

The fate of the Aral Sea provides a dangerous message for the world about land management and sustainable agriculture. Beginning in the 1960s, cotton production exploded. This was only achievable through the massive diversions of rivers. The fallout of this production is astounding. Today, we know that in the pursuit of cotton, the world lost its fourth largest lake. The Aral Sea communities lost so much more. They all but lost their fishing industries, and with that, a major staple of their diets. The climate turned volatile and health plummeted across hundreds of miles and millions of people. To avoid similar fates, people must become cognizant of how unsustainable water usage can lead to environmental and social devastation.

References

“Aral Sea.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Sept. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/place/Aral-Sea.

Carylsue. “Once Written Off for Dead, the Aral Sea Is Now Full of Life.” National Geographic Education Blog, 29 Mar. 2018, https://blog.education.nationalgeographic.org/2018/03/21/once-written-off-for-dead-the-aral-sea-is-now-full-of-life/.

Chen, Dene-Hern. “The Country That Brought a Sea Back to Life.” BBC Future, BBC, 23 July 2018, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180719-how-kazakhstan-brought-the-aral-sea-back-to-life.

Grabish, Beatrice. “Dry Tears of the Aral.” UN Chronicle, United Nations, 1999, https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/dry-tears-aral.

Hoskins, Tansy. “Cotton Production Linked to Images of the Dried up Aral Sea Basin.” Guardian News and Media, The Guardian, 1 Oct. 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2014/oct/01/cotton-production-linked-to-images-of-the-dried-up-aral-sea-basin.

“The Zoocenosis of the Aral Sea: Six Decades of Fast-Paced Change.” Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Changes-in-water-level-and-salinity-of-the-Aral-Sea-over-the-last-six-decades-based-on_fig4_329222649

“World of Change: Shrinking Aral Sea.” Earth Observatory, NASA, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/AralSea.